The Watch that Goes Tick-Tock

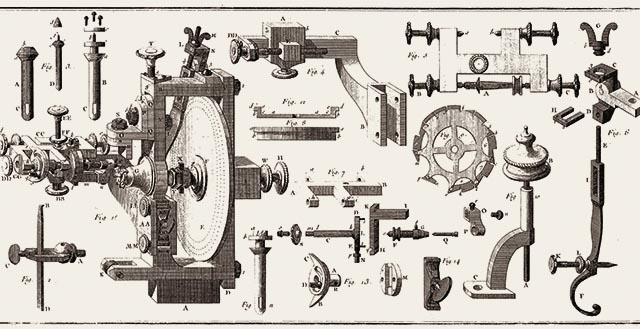

The typical sound of a mechanical timepiece comes from the escapement that stops the gear train at regular intervals in the course of its movement. The most significant developments in the field of escapements were made in England in the 18th century.

Around 1725 George Graham invented the cylinder escapement. The wheel only moves when an impulse is delivered, otherwise it remains motionless, which is why it is called a “dead-beat escapement”. This way, the precision of pocket watches could be increased to one minute per day. As a result, it made sense to have a second hand.

In 1757 Thomas Mudge designed an anchor escapement. It was given this name because of the shape of the impulse fork. When delivering the impulse, it establishes contact with the balance only briefly. Before and after this, the balance swings freely, which is why it is called a “free escapement”, the common escapement for today’s watches.

In 1782 John Arnold developed the chronometer escapement, also a “free escapement”. It only delivers an impulse with every second passage of the balance. Movements having a chrono-

meter escapement only make a “tick” sound; there is no “tock”. Timepieces constructed in this way attained a precision to within a few seconds per day as early as around 1800, even under harsh conditions.